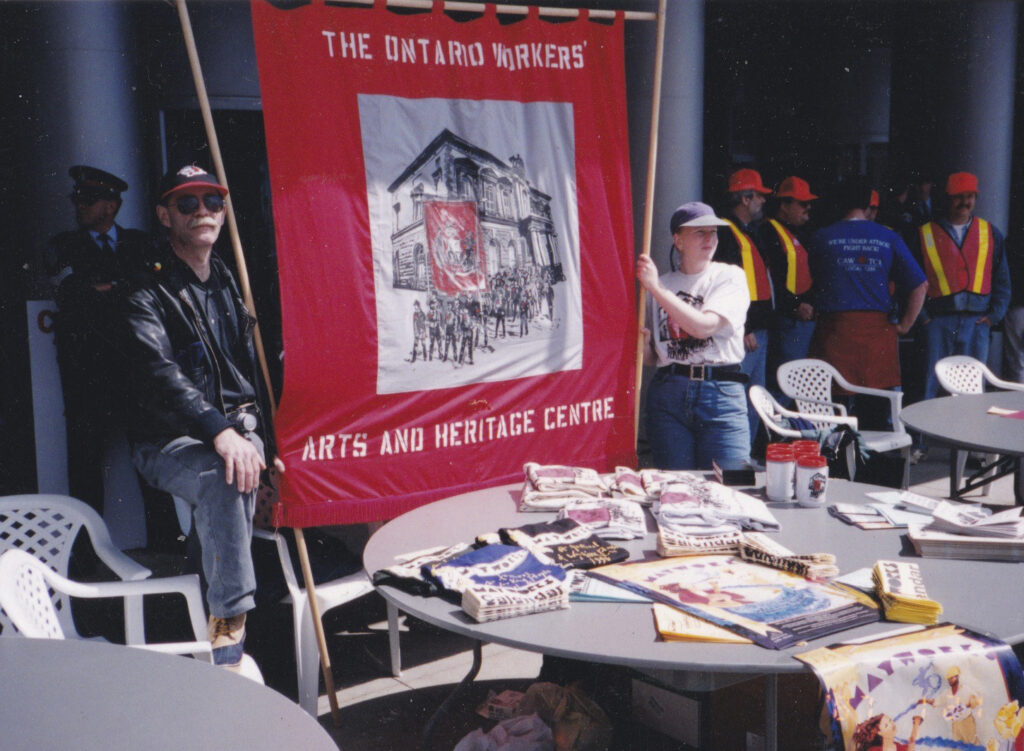

Artists Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge are two of the founders of the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre. They began working as independent conceptual artists in 1969, and have since exhibited work as a pair both nationally and internationally.

Condé and Beveridge are known for their photographic work depicting the stories of workers and activists, produced in collaboration with trade unions and community groups over the past 45 years. They have also been engaged in banner making since the 1980s.

Researcher Keely Shaw spoke with Condé and Beveridge in the Spring of 2023 to learn more about their work as labour artists, their interest in union banners, and how they came to create them as part of their art practice.

Keely Shaw: How did you get started as artists?

Condé and Beveridge: I guess [we] started out very early. Carole took lessons as a kid. We both ended up at the Ontario College of Art [now OCAD University], but only lasted a year or two because in those days one got out of art college as quickly as possible before they ruined you. [Carole and I] met soon after we left college. We started working independently, initially in Toronto; we had a place on Spadina Avenue. In 1969, we went to New York, because at that time, New York was, “the centre of the art world.”

While we were in New York, we became politicized. The interesting thing about New York is you [can see] the monster at its heart. You realize the dominance of the market, and how the market controlled what counted as art, and what was valued.

We realized that we needed to return to Canada because it’s the place we knew, it’s the culture we came out of. We returned to Toronto and became involved with political people here, some of whom we still are in contact with. And it was at that time that we started working with trade unions, and [taking an interest in] class politics. The first union we approached was United Steelworkers. Our first project was around the Radio Shack strike in Barrie in 1980. The next project we did after that was with autoworkers and the history of the General Motors Local 222 in Oshawa. We have worked with many other unions [since then].

How we became involved with banners is sort of interesting. When Carole was on a trip to England in the early 80s, our friends Peter Dunn and Lorraine Leeson took [her to] a small museum in London that had materials related to the English trade union movement, including a collection of banners. England has a very long tradition of producing elaborate banners for unions.

In 1980, [our friend Ian Bern] invited us to Australia, because he was working with the trade unions there. In Australia, they also had [a tradition of making elaborate fabric banners]. They were organizing the Artists in the Workplace program, along with the Australian trade unions. They approached the Australian Arts Council, and eventually got a $5 million program for artists to work with trade unions. Some of the most amazing banners were created in Australia throughout the 1980s.

In 1989, the Labour Arts and Working Group got the Ontario Arts Council [OAC] to establish a pilot program to fund artists working with trade union locals. In its first year, about 20 to 30 projects were done across the province. This program provided funding for all kinds of projects, including banners. And a number of banners were made by ourselves as well as other artists under the OAC’s Artists in the Workplace program.

On one of our trips to Australia, we met different people who made banners. One of them was an artist in Adelaide, Australia, named Kathy Muir, who had made a banner with public service workers. She visited Canada in 1990, and we set up a meeting [between her and] the Ontario Federation of Labour Cultural Committee. They were so impressed with the Australian contemporary banners that they instituted a banner competition among affiliates to reward the best banner made each year. This helped kickstart the production of trade union banners through the 1990s. We did about 15. I think there are another 15 to 20 that were done by other artists. So there were a lot of trade union banners done in that period up, into the 2000s.

Keely Shaw: Did you choose to focus on banners because of their historical use?

Condé and Beveridge: Our photographic work is our primary work. Our interest in banners developed after we did a banner for the Ontario Federation of Labor for their banner competition in 1990. Carole wanted to do it. Banners became interesting, not only as an artistic focus, but also, for us, an economic one.

The thing about banners was that the unions wanted them so much that they were willing to pay for them. Carrying a banner was a source of pride.

Keely Shaw: There are a lot of different things happening in your banners, materials-wise. Can you talk about the decisions you make about this?

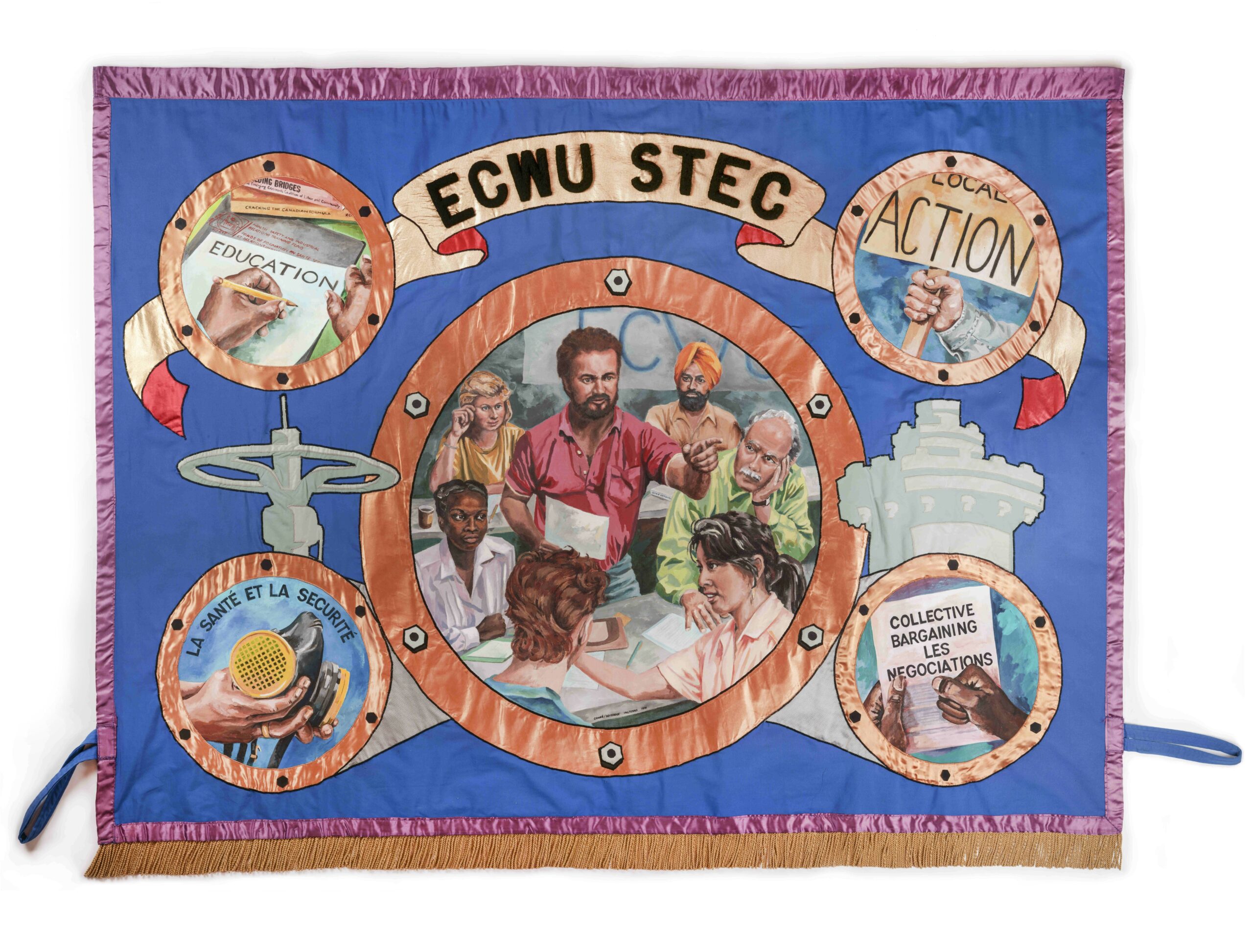

Condé and Beveridge: We work off the tradition of banner making, while interpreting it in a more contemporary way. The Energy and Chemical Workers Union banner [depicts] pipelines and energy – we use those kinds of images to create the design while working with characters. [This banner] was probably not as radical as some of the more offbeat Australian banners, but it was trying to sort of balance readability with design and symbolism. [We] add other layers to that, like we do in [our] photographs. We try to include or incorporate commentary. [Some banners are about] ideas, as well as about whatever the scene is.

This interview is excerpted from an oral history interview between Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge and researcher Keely Shaw. It has been edited for clarity and length.