The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) was founded in the United States of America in 1900. Throughout its history, ILGWU was known for its “social unionism.” Its work extended beyond advocating for better workplace conditions, and into the creation of arts and education, health care, cooperative housing, immigration support, and recreation opportunities for its members.

Between December 1910 and the end of 1911, the ILGWU established six Canadian locals in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg. Despite early gains, the road to unionizing garment workers in Canada was long and difficult. Between the ILGWU and another garment workers’ union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), only about a quarter of workers in the needle trades had unionized by the 1920s. In contrast, approximately half of the workforce had unionized by 1937.

The Eaton’s strike of 1912 in Toronto, was the first major strike action conducted by ILGWU in Canada. In March 1912, 65 men who worked as machine operators sewing coats refused to follow new orders to complete finishing work, which owner Timothy Eaton demanded without offering an increase in pay. Finishing, the process of attaching coat linings, was done by hand, typically by women who were not in the union. After the men refused to take on the finishing work, Eaton locked out the workers and refused to negotiate with their union.

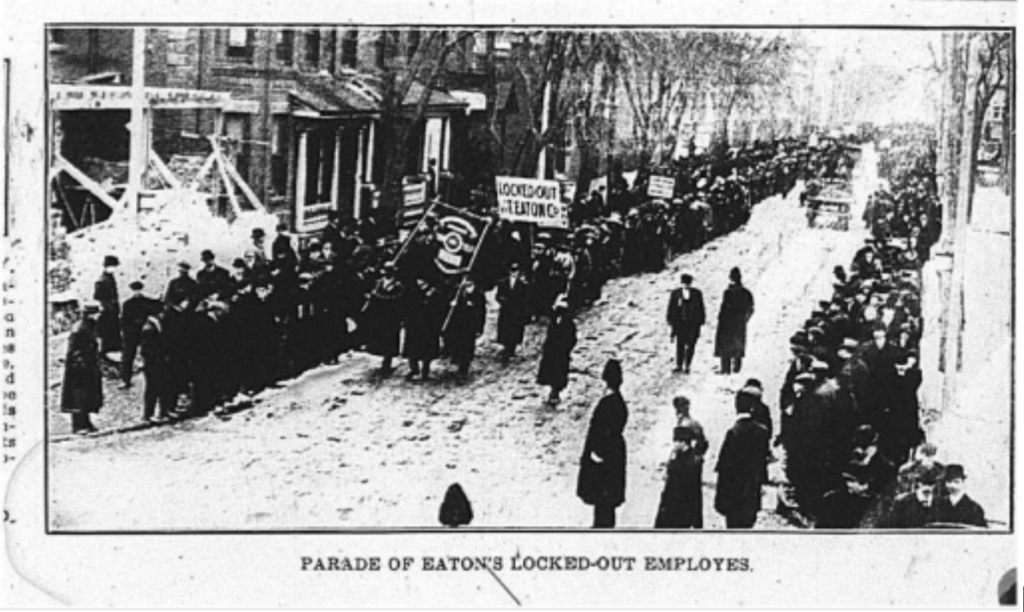

One thousand garment workers walked out in support of the 65 cloak makers. By March 23rd, over 2,000 strike supporters joined a demonstration in Toronto, which included children and elderly community members. The demonstration took the form of a parade which began at the Labour Temple on Church Street, travelling west along Queen Street. The march continued up Spadina Avenue and east along College Street, culminating in a rally at Massey Hall.

Workers at the Eaton’s clothing factory in Montreal went on strike in solidarity, and Hamilton’s garment workers threatened to join the strike if any of their companies attempted to do work for Eaton’s. There was also a call for a nationwide boycott of Eaton’s goods.

The boycott was particularly effective in Toronto’s immigrant Jewish community. The Toronto District Labour Council asked for women’s clubs and groups to join the boycott, however support stalled across class lines when women from the leisure class did not support the strike or boycott.

Despite the efforts of strikers and demonstrators, the strike broke after four months without a deal. The ILGWU found itself weakened, and Eaton’s refused to hire Jewish people. Even so, hope remained in the wake of the Eaton strike; it had been a moment of solidarity across gender lines, and had mobilized Toronto’s Jewish working class. One of the slogans of the strike was “Mir vellen nisht aroycenemen dem bissle fun broyt fun di mayler fun undzere shvester,” which translates into English as “We will not take the morsel of bread from the mouths of our sisters.”

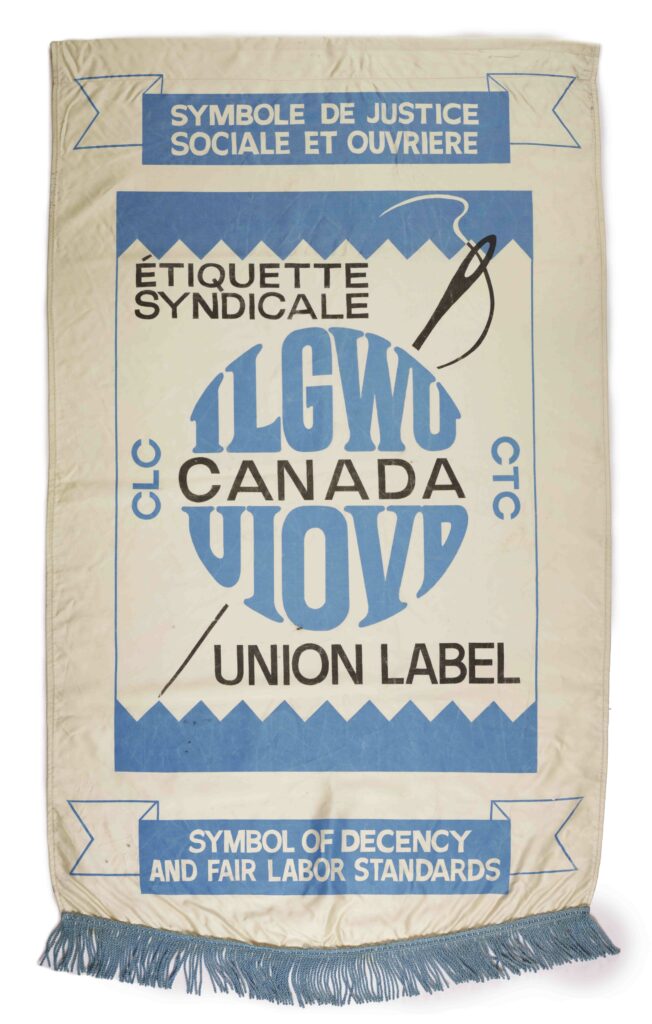

While the majority of WAHC’s ILGWU banners are thought to be from the 1930s, one appears to be similar to one carried at the Eaton’s parade in 1912. Another exceptional piece in WAHC’s collection is a small bilingual banner, likely from Quebec, illustrating the ILGWU union label.

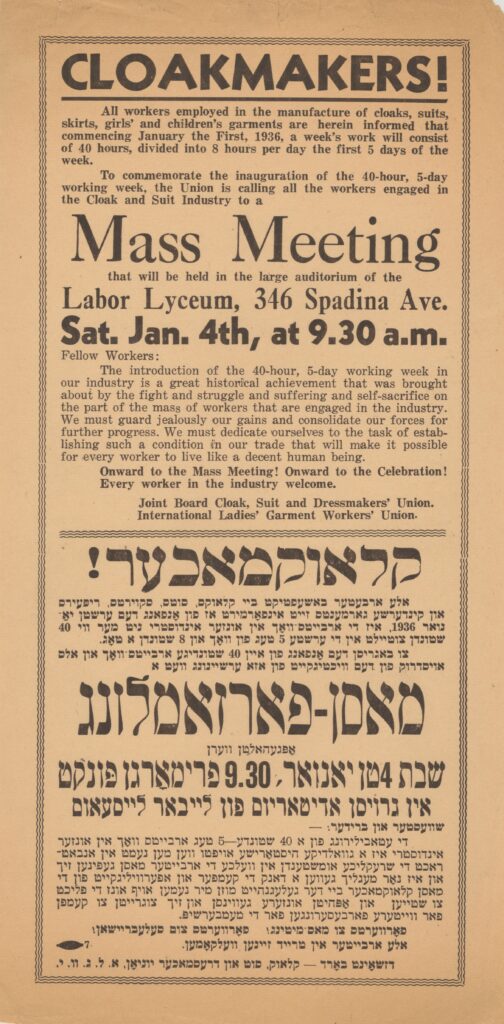

According to a convention report, the inclusion of a label on all ILGWU-made goods was a priority of the union as far back as 1910. By the 1970s and 1980s, the decline of garment manufacturing in North America was accelerating, due to increased importation of goods made overseas. Part of the ILGWU’s response to this trend was a Union Label campaign, which included promotion of its Union Label in print, radio, and on television. Their well known “Union Label song” in campaign ads appealed to shoppers’ desire for quality, and promoted the benefits of supporting domestic garment workers. The ILGWU even produced and distributed films that highlighted the fashion appeal of garments produced by ILGWU members.

Despite these efforts, Canada saw a drastic decline in textile and garment jobs, losing hundreds of thousands of workers by the late 1980s. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA), continued to contribute to the loss of thousands of jobs in the garment industry in Canada throughout the 1990s. In 1995, the ILGWU merged with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union to form UNITE. Now known as UNITE HERE, this union brings together workers from the garment industry, hotels, restaurants, racetracks and casinos, laundry, and food service companies.

Sources

Katheryn Dowgiewicz, The ILGWU Internationally: The ILGWU In Canada. The Kheel Center ILGWU Collection. Online. Accessed October 2023. https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/announcements/27.html

Ruth A. Frager, “Sewing Solidarity: The Eaton’s Strike of 1912,” in A Nation of Immigrants: Women, Workers, and Communities in Canadian History, 1840s-1960s, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 317.

Mercedes Steedman, “Canada’s New Deal in the Needle Trades: Legislating Wages and Hours of Work in the 1930s,” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 53, 3 (1998, Summer), 536.

UNITE HERE Local 75 website. https://www.uniteherelocal75.org